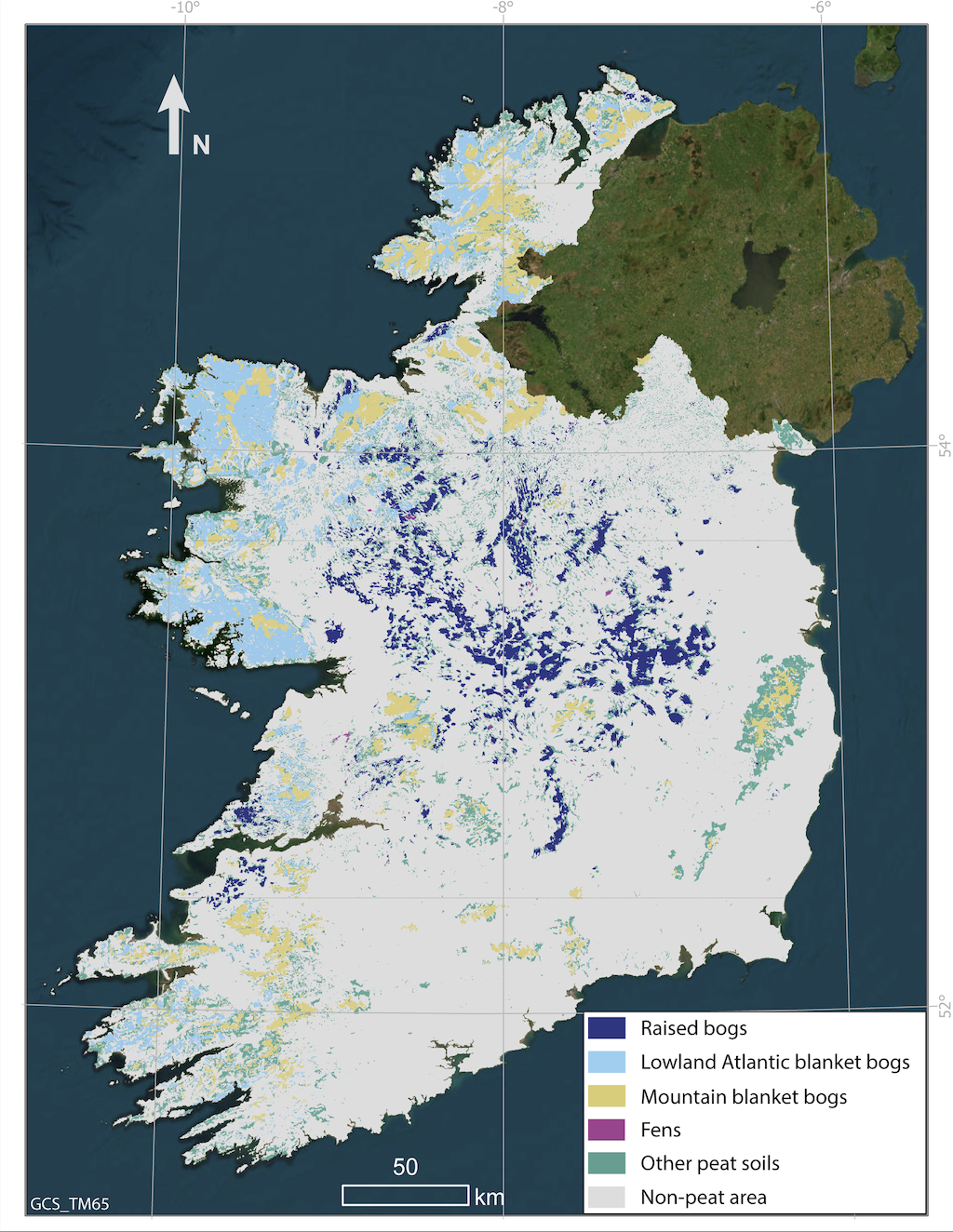

Raised bogs are discreet, raised, dome-shaped masses of peat occupying former lakes or shallow depressions in the landscape. They occur throughout the midlands of Ireland. Their principal supply of water and nutrients is from rainfall and the substrate is acid peat soil, which can be up to 12m deep. Raised bogs are characterised by low-growing, open vegetation dominated by mosses, sedges and heathers, all of which are adapted to waterlogged, acidic and exposed conditions.

Raised bogs are discreet, raised, dome-shaped masses of peat occupying former lakes or shallow depressions in the landscape. They occur throughout the midlands of Ireland. Their principal supply of water and nutrients is from rainfall and the substrate is acid peat soil, which can be up to 12m deep. Raised bogs are characterised by low-growing, open vegetation dominated by mosses, sedges and heathers, all of which are adapted to waterlogged, acidic and exposed conditions.

|

Download a copy of the IPCC’s My Raised Bogs booklet to find out how you can help to save these wonderful habitats here. |

Distribution of Raised Bogs in Ireland

Raised bogs are a distinctive and characteristic feature of the landscape of the midlands of Ireland in which they are concentrated. They also occur in the Bann River Valley in Northern Ireland, in the vicinity of Omagh, Co. Tyrone, and in East Clare and North Limerick on either side of the mouth of the River Shannon. They occur on land below 130m and in that climatic zone where rainfall is between 800 and 900mm per year.

Formation of Raised Bogs

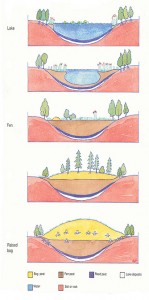

Raised bogs began to develop 10,000 years ago in depressions occupied by shallow lakes in which anaerobic conditions occurred. Complete decomposition of plant material is prevented. In time this un-decomposed plant material forms a thick layer of peat that rises towards the surface of the lake. Eventually the surface peat is invaded by sedges to form a fen. The fen peat layer thickens so that the roots of plants growing on the surface are no longer in contact with the calcium-rich groundwater. The only source of minerals for plants is now rainwater, which is very poor in minerals. Raised bog species, such as Sphagnum mosses begin to invade and eventually the fen becomes a raised bog

Raised bogs began to develop 10,000 years ago in depressions occupied by shallow lakes in which anaerobic conditions occurred. Complete decomposition of plant material is prevented. In time this un-decomposed plant material forms a thick layer of peat that rises towards the surface of the lake. Eventually the surface peat is invaded by sedges to form a fen. The fen peat layer thickens so that the roots of plants growing on the surface are no longer in contact with the calcium-rich groundwater. The only source of minerals for plants is now rainwater, which is very poor in minerals. Raised bog species, such as Sphagnum mosses begin to invade and eventually the fen becomes a raised bog

Raised Bog Structure and Hydrology

In raised bogs water peat and vegetation are strongly interconnected

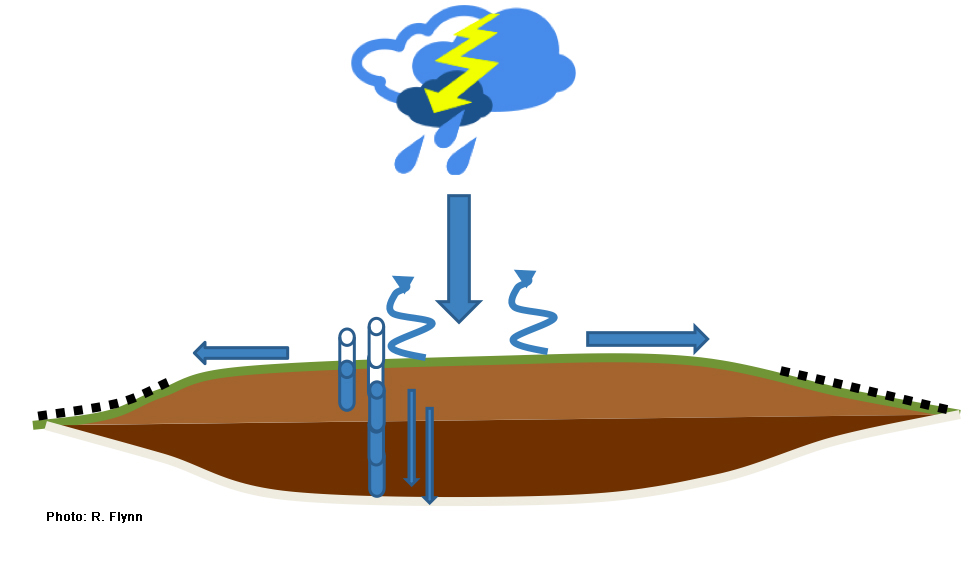

Water in a raised bog is continuously circulating and changing even though it looks the same. A healthy bog eco-hydrology is nutrient poor and waterlogged on the surface. The principal supply of water and nutrients in a raised bog is from rainfall. Rain reaching the surface of the raised bog is lost through evapo-transpiration from the plants that grow there. More water is lost through surface runoff. In a naturally undisturbed bog where slopes are shallow, rainwater slowly travels across the surface of the bog. If the slopes on the bog are increased through marginal drainage water runs off the bog dome rapidly. If water is leaving the bog more quickly than it can be recharged from rainfall, this causes a deterioration in the natural peat forming capability of the bog.

In a natural bog more water is also lost from the bottom of the bog through seepage. Depending on the intensity of drainage, a lot of water may be lost out through the bottom of the bog. This happens if marginal drains cut through the natural clay liner that occurs in the bottom of raised bogs. Bogs that have formed over sands, silts and gravels without a clay liner are very susceptible to water loss in this way.

The diagram below drawn by Dr Ray Flynn of Queens University in Belfast shows how water behaves in a raised bog.

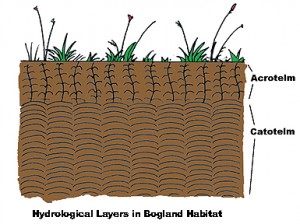

The surface of a raised bog consists of a soft living carpet of vegetation, which floats on a material, which is nearly all water. By weight, a raised bog may be up to 98% water and only 2% solid matter. This volume of water is held within dead Sphagnum moss fragments. Raised bogs consist of two hydrological layers (see figure inset); the upper, very thin layer, known as the acrotelm, is usually less than 50cm deep, and consists of living stems of Sphagnum mosses, recently dead plant material and water. The acrotelm has high permeability to water near to the surface, but becomes more impermeable with depth as the peat becomes more consolidated and decomposed (humified). Water movement and fluctuations mean that conditions in the acrotelm remain largely aerobic and it is here that microbial activity is strongest. These properties mean that the acrotelm is critical to the normal development and functioning of a raised bog. Below this is a very much thicker bulk of peat, known as the catotelm, where individual plant stems have collapsed under the weight of mosses above them to produce an amorphous, chocolate-coloured mass of Sphagnum fragments. By contrast with the acrotelm, catotelm peat is typically well consolidated and often strongly humified. It is permanently saturated with water. Water movement through this amorphous peat is very slow, typically less than a meter a day. This is where most of the rain water is stored.

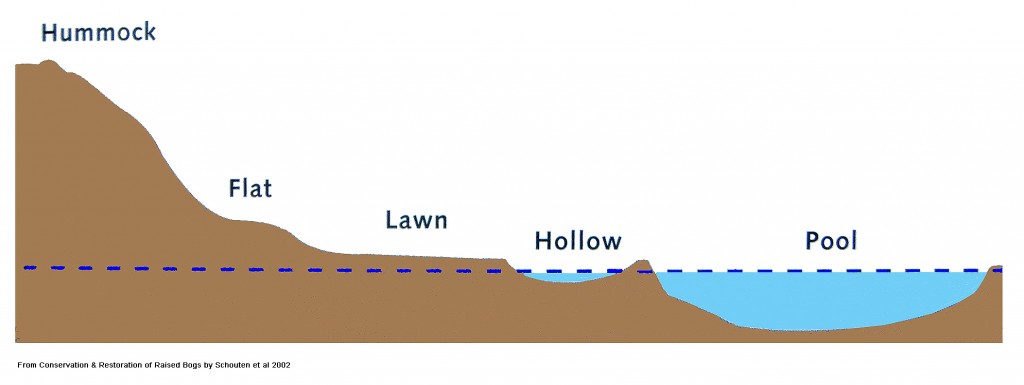

In a raised bog, which is ombrotrophic, the only source of water to the surface is from precipitation. Under normal circumstances the water table is very stable, remaining within a few centimetres of the bog’s surface about 95% of the time. Because the surface of a bog typically consists of low hummocks, hollows and pools, this stable water table produces intense competition for living space between species.

Raised Bog Ecotopes

With active Sphagnum growth, raised bogs develop a system of hummocks, pools and hollows with flat areas and lawns in between. The water level is at or near the surface. Slopes are gentle, Sphagnum mosses form a complete growth pattern over the surface of the bog.

With active Sphagnum growth, raised bogs develop a system of hummocks, pools and hollows with flat areas and lawns in between. The water level is at or near the surface. Slopes are gentle, Sphagnum mosses form a complete growth pattern over the surface of the bog.

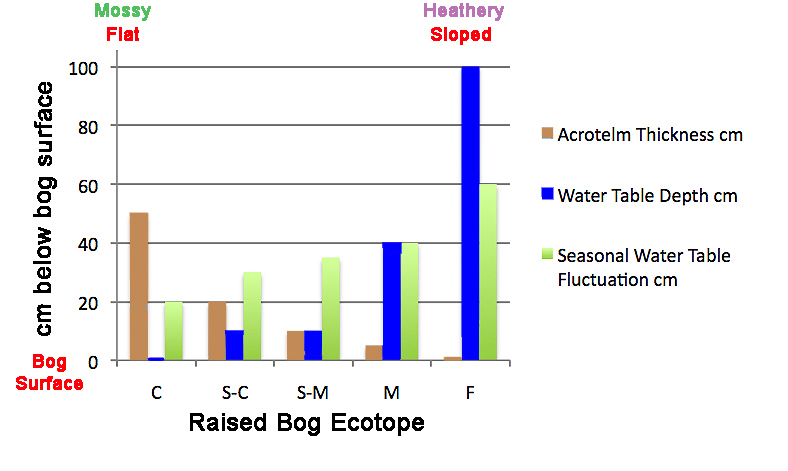

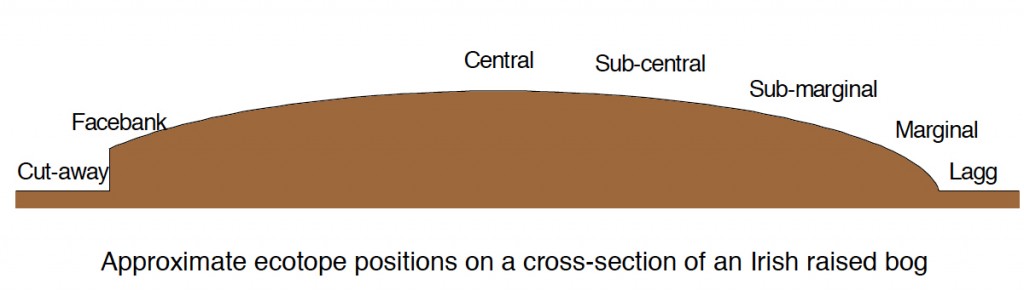

From the air raised bogs look patterned, reflecting their micro-topography or certainly the contrast between pools and hummocks. On the ground the micro-topography of raised bogs determines the types of plant communities that are present. The scale of raised bog communities is very small: for example 20cmx40cm is typical for hollows and pools while 100cmx100cm is the size of hummock communities. This has given rise to the idea of a community complex to describe an area of hummock and hollow complex on a raised bog. Community complexes are strongly correlated with the abiotic conditions prevailing particularly hydrological conditions such as water level, nutrient supply, drainage and slope on the raised bog. It is the combination of the biotic and abiotic components that defines an ecotope. The ecotope is very useful for discussion of raised bog management because it is based on an ecohydrological approach. The different ecotopes found on a raised bog are shown in the diagram below. The central and sub-central ecotopes are actively forming peat.

The concept of the ecotope was developed by Irish and Dutch researchers working on Clara and Raheenmore Bogs in Co. Offaly over a 10 year period. A book entitled Conservation and Restoration of Raised Bogs edited by Matthijs Schouten and published in 2002 describes the results of this joint Irish-Dutch research project in detail. The basic ecotopes system is founded on a concentric approach from the centre to the margin of a raised bog. The characteristics of the five common ecotopes found on Irish raised bogs are shown in the chart below. The presence and thickness of the Sphagnum moss layer or acrotelm is critical for peat formation. It is best developed in the Central ecotope. An acrotelm is very sensitive to drainage and fire and it is absent in the facebank ecotope where, for example, turf is cut.

The concept of the ecotope was developed by Irish and Dutch researchers working on Clara and Raheenmore Bogs in Co. Offaly over a 10 year period. A book entitled Conservation and Restoration of Raised Bogs edited by Matthijs Schouten and published in 2002 describes the results of this joint Irish-Dutch research project in detail. The basic ecotopes system is founded on a concentric approach from the centre to the margin of a raised bog. The characteristics of the five common ecotopes found on Irish raised bogs are shown in the chart below. The presence and thickness of the Sphagnum moss layer or acrotelm is critical for peat formation. It is best developed in the Central ecotope. An acrotelm is very sensitive to drainage and fire and it is absent in the facebank ecotope where, for example, turf is cut.

Importance of Raised Bogs

Raised bogs are beautiful landscapes with a unique biodiversity. They provide mankind with services that are worth billions of euro that may be easily jeopardised by inappropriate or short-sighted exploitation. Raised bogs are:

- the finest example of their type in Europe, and probably the world

- a unique repository of information of past climates, vegetation and human activity

- a valuable genetic resource of potential use to humanity

- valuable outdoor laboratories in which plants, animals and natural processes in an extremely inhospitable environment can be studied

- of national and international importance as part of the biosphere in which they are inextricably linked to to other ecosystems

- a unique feature of the Irish landscape of considerable tourist value

- a priority habitat under the EU Habitats Directive because of their scarcity in Europe

- an important store of carbon, helping to control greenhouse gases

- an important store of water within river catchments

Conservation Status of Irish Raised Bogs

Under the EU Habitats Directive the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) are obliged to complete a report every 7 years on the condition of designated habitats. The assessments carried out in 2006 and in 2013 found that no peatland type of priority importance in Ireland is in good conservation status. Raised bogs have been given a BAD status in these reports because of a significant decrease in their range, habitat structure, habitat function and area.

Extent and Utilisation of Raised Bog

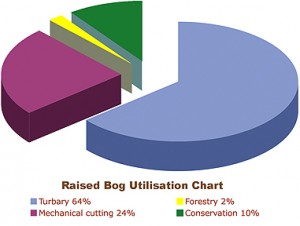

The original extent of raised bog in the Republic of Ireland was 308,742ha according to the Peatland Map of Ireland drawn by Hammond in 1979. IPCC monitors the status of the resource on an on going basis. Our latest assessment was carried out in 2009 and published in Ireland’s Peatland Conservation Action Plan 2020. Developmental pressures on raised bogs are intense, particularly extraction for fuel and horticulture mainly due to the development of new markets for these products and the establishment of numerous peat producing businesses. The most serious impact of mechanised peat extraction in Ireland has been on the Midland raised bogs accounting for a loss of 24% of the resource in less than 50 years. Hand peat cutting accounts for a staggering 64% loss and afforestation accounts for 2% of the loss of habitat in the Republic of Ireland. This leaves 10% of the raised bogs remaining which are deemed suitable for conservation.

The original extent of raised bog in the Republic of Ireland was 308,742ha according to the Peatland Map of Ireland drawn by Hammond in 1979. IPCC monitors the status of the resource on an on going basis. Our latest assessment was carried out in 2009 and published in Ireland’s Peatland Conservation Action Plan 2020. Developmental pressures on raised bogs are intense, particularly extraction for fuel and horticulture mainly due to the development of new markets for these products and the establishment of numerous peat producing businesses. The most serious impact of mechanised peat extraction in Ireland has been on the Midland raised bogs accounting for a loss of 24% of the resource in less than 50 years. Hand peat cutting accounts for a staggering 64% loss and afforestation accounts for 2% of the loss of habitat in the Republic of Ireland. This leaves 10% of the raised bogs remaining which are deemed suitable for conservation.

Conserving Raised Bogs

In the Republic of Ireland the National Parks and Wildlife Service of the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht are the Government agency responsible for the conservation of raised bogs. Major field surveys have been undertaken so that the raised bogs of conservation importance could be identified from 1983 to the present day. Initially sites were designated as Areas of Scientific Interest. Thereafter sites were identified as Natural Heritage Areas, some of which were then designated as Special Areas of Conservation under the EU Habitats Directive.

Between 1997 and 2002, Ireland nominated a total of 53 raised bog sites for designation as Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) under the Habitats Directive. Ireland must protect, manage and restore these sites to ensure they achieve their objective of conserving raised bog habitats and species. In addition, 75 raised bogs were designated as Natural Heritage Areas (NHAs) in 2004 under the Wildlife Amendment Act (2000).

Most sites were designated without adequate consultation with the tens of thousands of landowners who retained their right to cut turf in these sites. Rather than acquiring control of turf cutting areas within raised bogs to create manageable hydrological units, the Government put in place a derogation which essentially allowed turf cutting to continue on sites of conservation importance for a minimum period of 10 years. During this period a limited number of turf cutting rights were acquired from landowners on sites, however, in the case of most sites not all turf cutting rights were acquired. Once the deadline for the cessation of turf cutting was reached, landowners who retained turf cutting rights refused to stop cutting turf. As a result of the Government’s failure to protect raised bogs from turf cutting and drainage, the area of active raised bog in the country is less than 4,000ha today.

In parallel with the public unrest in relation to raised bog conservation within the country, the European Union took a number of cases against Ireland for infringements of EU law. The Court of Justice of the European Union have threatened to fine the country for their lack of compliance.

Against this background, in 2013, the Irish Government launched a study to provide a scientific basis for raised bog conservation in Ireland. The study is expected to be completed in 2015. The first documents to be produced from the study were the Draft Raised Bog SAC Management Plan and the Draft Raised Bog NHA Review. These went out to public consultation in 2014. The Raised Bog SAC Management Plan 2016-2021 is due to be published shortly. Several key decisions in relation to the conservation and management of raised bogs are contained within these documents:

Against this background, in 2013, the Irish Government launched a study to provide a scientific basis for raised bog conservation in Ireland. The study is expected to be completed in 2015. The first documents to be produced from the study were the Draft Raised Bog SAC Management Plan and the Draft Raised Bog NHA Review. These went out to public consultation in 2014. The Raised Bog SAC Management Plan 2016-2021 is due to be published shortly. Several key decisions in relation to the conservation and management of raised bogs are contained within these documents:

- A national conservation target for active raised bog amounting to 3,600ha has been set.

- The NHA network of 75 sites established in 2004 has been reconfigured and a new network has been established which will contain 61 sites (36 of the existing NHAs are to be retained, 25 previously undesignated sites are being proposed for NHA status, all or part of 46 previously designated NHAs are to be de-designated which will necessitate new legislation).

- The conservation and management of raised bogs will follow a six year progress and review cycle.

- Turf cutting is to be allowed on one raised bog SAC.

- Turf cutting is to be allowed to continue on all 61 NHAs in the new network until 2017.

- The key management strategy for raised bogs is to block drains so as to bring the water levels in the bog back up to the surface.